Artists across China are boycotting one of the country’s biggest social media platforms over complaints about its AI image generation tool.

The controversy began in August when an illustrator who goes by the name Snow Fish accused the privately owned social media site Xiaohongshu of using her work to train its AI tool, Trik AI, without her knowledge or permission.

Trik AI specializes in generating digital art in the style of traditional Chinese paintings; it is still undergoing testing and has not yet been formally launched.

Snow Fish, whom CNN is identifying by her Xiaohongshu username for privacy reasons, said she first became aware of the issue when friends sent her posts of artwork from the platform that looked strikingly similar to her own style: sweeping brush-like strokes, bright pops of red and orange, and depictions of natural scenery.

“Can you explain to me, Trik AI, why your AI-generated images are so similar to my original works?” Snow Fish wrote in a post which quickly circulated online among her followers and the artist community.

The controversy erupted just weeks after China unveiled rules for generative AI, becoming one of the first governments to regulate the technology as countries around the world wrestle with AI’s potential impact on jobs, national security and intellectual property.

Trik AI and Xiaohongshu, which says it has 260 million monthly active users, do not publicize what materials are used to train the program and have not publicly commented on the allegations. The companies have not responded to multiple requests from CNN for comment.

But Snow Fish said a person using the official Trik AI account had apologized to her in a private message, acknowledging that her art had been used to train the program and agreed to remove the posts in question. CNN has reviewed the messages.

However, Snow Fish wants a public apology. The controversy has fueled online protests on the Chinese internet against the creation and use of AI-generated images, with several other artists claiming their works had been similarly used without their knowledge.

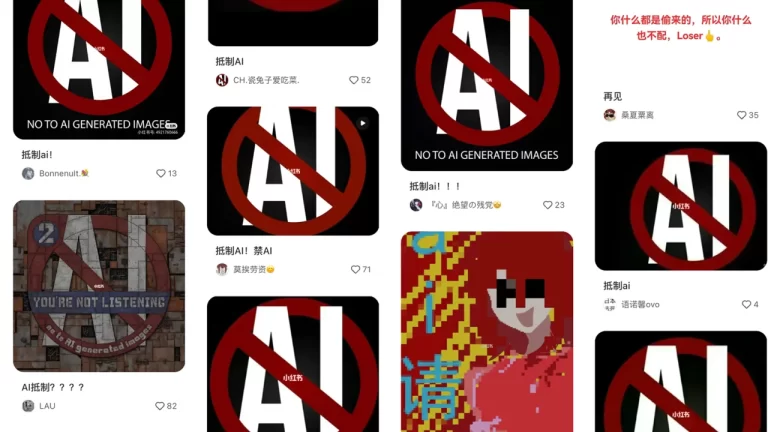

Hundreds of artists have posted banners on Xiaohongshu saying “No to AI-generated images,” while a related hashtag has been viewed more than 35 million times on the Chinese Twitter-like platform Weibo.

The boycott in China comes as debates about the use of AI in arts and entertainment are playing out globally, including in the United States, where striking writers and actors have ground most film and television production to a halt in recent months over a range of issues — including studios’ use of AI.

Artists speak out

Many of the artists boycotting Xiaohongshu have called for better rules to protect their work online — echoing similar complaints from artists around the world worried about their livelihoods.

These concerns have grown as the race to develop AI heats up, with new tools developed and released almost faster than governments can regulate them — ranging from chatbots such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT to Google’s Bard.

China’s tech giants, too, are rapidly developing their own generative artificial intelligence, from Baidu’s ERNIE Bot launched in March to SenseTime’s chatbot SenseChat. Besides Trik AI, Xiaohongshu has also developed a new function called “Ci Ke” which allows users to post content using AI-generated images.

For artists like Snow Fish, the technology behind AI isn’t the problem, she said; it’s the way these tools use their work without permission or credit. Many AI models are trained from the work of human artists by quietly scraping images of their artwork from the internet without consent or compensation.

Snow Fish added that these complaints had been slowly growing within the artist community but had mostly been privately shared rather than openly protested.

“It’s an outbreak this time,” she said. “If it easily goes away without any splash, people will maintain silent, and those AI developers will keep harming our rights.”

Another Chinese illustrator Zhang, who CNN is identifying by his last name for privacy reasons, joined the boycott in solidarity. “They’re shameless,” said Zhang. “They didn’t put in any effort themselves, they just took parts from other artists’ work and claimed it as their own, is that appropriate?”

“In the future, AI images will only be cheaper in people’s eyes, like plastic bags. They will become widespread like plastic pollution,” he said, adding that tech leaders and AI developers care more about their own profits than about artists’ rights.

Tianxiang He, an associate professor of law City University of Hong Kong, said the use of AI-generated images also raises larger questions among the artistic community about what counts as “real” art, and how to preserve its “spiritual value.”

Similar boycotts have been seen elsewhere around the world, against popular AI image generation tools such as Stable Diffusion, released last year by London-based Stability AI, and California-based Midjourney. Stable Diffusion is embroiled in an ongoing lawsuit brought by stock image giant Getty Images, alleging copyright infringement.

Race to regulate AI

Despite the speed at which AI image generation tools are being developed, there is “no global consensus about how to regulate this kind of training behavior,” said He. He added that many such tools are developed by tech giants who own huge databases, which allows them to “do a lot of things … and they don’t care whether it’s protected by the law or not.”

Because Trik AI has a smaller database to pull from, the similarities between its AI-generated content and artists’ original works are more obvious, making an easier legal case, he said. Cases of copyright infringement would be harder to detect if more works were put in a larger database, he added.

Governments around the world are now grappling with how to set global standards for the wide-ranging technology. The European Union was one of the first in the world to set rules in June on how companies can use AI, with the United States still holding discussions with Capitol Hill lawmakers and tech companies to develop legislation.

China was also an early adopter of AI regulation, publishing new rules that took effect in August. But the final version relaxed some of the language that had been included in earlier drafts. Experts say major powers like China likely prioritize centralizing power from tech giants when drafting regulations, and pulling ahead in the global tech race, rather than focusing on individuals’ rights.

He, the Hong Kong law professor, called the regulations a “very broad general regulatory framework” that provide “no specific control mechanisms” to regulate data mining.

“China is very hesitant to enact anything related to say yes or no to data mining, because that will be very dangerous,” he said, adding that such a law could strike a blow to the emerging market, amid an already slow national economy.

— CutC by cnn.com